As a Bostonian, the last place I wanted to go for vacation in January was Alberta, Canada. Going from cold to colder is not my idea of fun and relaxation. But, despite my trepidation and initial perceptions, I must admit that the Canadian Rockies in the middle of winter is absolutely beautiful. Of course, while I was there, I took the opportunity to explore the local drink culture, and in particular, Canadian whisky. Over the past few years, Canadian whisky has been getting more attention in the global whisky conversation–thanks to folks like Davin de Kergommeaux (author of the book Canadian Whisky)–and in turn, it has made me want to take a harder look. So, that’s exactly what I did. Because why would you want to go out in the freezing snow when there is whisky and heat inside?

A few interesting facts about Canadian whisky:

There are a number of really interesting facts about Canadian whisky that may surprise you—both in regards to how it’s made and how popular it actually is. The first thing to know, to set the stage, is that from 1865 to 2010, Canadian whisky was the best selling whisky in the US. In 2010, Bourbon finally took the throne (and rightfully so), but it was a hell of a long reign. For you Bourbon and Scotch drinkers, this may be a hard fact to process. But when you think of some of the big Canadian whisky names—Canadian Club, Seagram’s, Crown Royal—perhaps it’s not such a hard fact to get your head wrapped around after all.

One of the major differences between Canadian whisky and American whiskey is in how grains are treated. Both countries use many of the same grains to make their whisk(e)y—corn, wheat, rye—but where the Bourbon industry blends their grains at the beginning of the production process (to create a mash bill), Canadian whisky makers blend their grains at the end. So, in Canada, rye (for instance) is milled, mashed, fermented, distilled and matured on its own. The same goes for corn, wheat and barley malt. There are a couple major distilleries that blend just prior to aging, but that’s an exception, not the norm.

Another interesting fact is that Canadian whiskies are typically produced from two whisky streams. A base whisky is distilled to a higher alcohol content to bring out the flavors of the wood and a flavoring whisky is distilled to a lower alcohol content to bring out more of the grain-derived flavors of the spirit. The two streams are blended together after maturation to create the end whisky. Some distilleries actually only make one base whisky for their line of products, so that flavoring element can play a big role in the final product.

Canadian distilleries

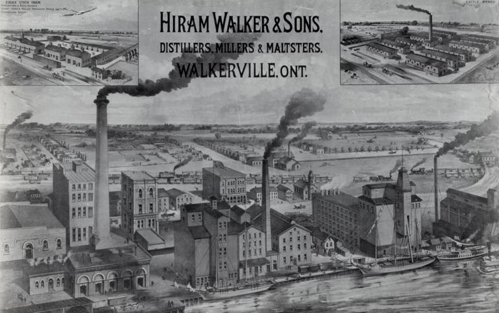

In Canada, there are only eight major commercial distilleries spread out across the provinces (plus a few dozen smaller craft distilleries). This is in stark difference to the landscape in America and in Scotland which have about 600+ and 120+, respectively. In short, there are three distilleries in Alberta: Alberta Distillers, Black Velvet and Highwood; one in Manitoba: Gimli (makers of Crown Royal); three in Ontario: Canadian Mist, Hiram Walker & Sons (makers of Wiser’s and Canadian Club) and Forty Creek; and one in Quebec: Valleyfield (makers of Seagram’s).

Why do Canadians call their whisky “rye?”

One of the strangest things I find about Canadian whisky (from my American perspective, of course) is that Canadians refer to their whisky as “rye.” I went into a few liquor stores when I was in Canada the other week and, without fail, every store labeled their Canadian whisky section “Rye.” The odd part about this is that the most common grain used in Canadian whisky is corn. In fact, rye is typically used only as a flavoring element.

In order to uncover the mystery behind this fact, you have to look into the history of whisky in Canada. So the story goes, Canadian flour millers began making whisky with excess wheat two centuries ago. Somewhere along the way, someone decided to spice things up by adding a little rye grain. This new rye-spiced version of whisky caught on like wildfire and quickly came to dominate whisky sales in the country. In turn, Canadians started referring to their whisky as rye; again despite the fact that rye was just a flavoring element.

You can, of course, find actual 100% rye whiskies in Canada. Lot No. 40 and Alberta Premium are two good examples from the major distillers.

On to the Tasting

Because there are only eight major commercial distilleries in Canada (and only a handful of craft distilleries), getting into Canadian whisky can be a good deal less intimidating than getting into Scotch or American whiskey. But the question is still valid: how does one dive in?

When I was in Canada last week, I was asked to host an introductory tasting for a group of doctors. My strategy for putting the lineup together was to select a number of well-regarded Canadian whiskies and try to get a good representation from the major distillers, as well as a few whiskies that were available also in the US.

My selections included: Wiser’s Legacy, Alberta Premium Dark Horse, Lot No. 40, Ninety 20yr, Pike Creek, and Wiser’s Red Letter. There were a few whiskies I was looking for that I couldn’t find, which would have helped to diversify further (but they were sold out in the province)—specifically: Forty Creek Double Barrel and Gibson’s Finest Rare 18 year. There were also three whiskies, Caribou Crossing, Collingwood 21 and Masterson’s 10yr, which weren’t available at all in Alberta. All of these whiskies would make a good choice for starting your Canadian whisky collection.

Here are the tasting notes and my reviews:

Lot No. 40 (Hiram Walker & Sons):

I started the tasting with Lot No. 40 because it’s made from 100% rye and it’s the Canadian whisky I’m most familiar with. It also won Whisky Advocate’s 2012 Canadian Whisky of the Year, so figured we’d start strong. Lot No. 40 is available in both Canada and the US, and sells for about $55.

Nose: This whisky bursts with dusty rye, molasses, wood notes and dark fruit.

Palate: A big mouthful of rye spice, dark fruit, oak, a little orange and hot pepper.

Overall: This is a really nice expression of rye regardless of the origin, but an easy recommendation for a Canadian whisky. 89 Points

Ninety 20yr (Highwood):

I put this whisky right behind Lot No. 40 because it’s a 100% corn whisky and clearly shows the difference between the two grains. Ninety 20yr is a Canada-only release, and was introduced to the market in 2013. It sells for about $50 (which is insanely low compared to 20 year whiskies anywhere else in the world).

Nose: Butterscotch, corn syrup, cream and cloves.

Palate: The whisky is creamy and sweet, with pepper and baking spices. There’s some sour fruit and long-aged oak notes as well, but it’s that cooked corn that really comes through from start to finish.

Overall: It’s hard to mistake this whisky for anything other than corn-based. It is a much softer and “prettier” whisky than the Lot No. 40, which you’d expect from corn versus rye. For those that like this softer, sweeter style, you’ll likely enjoy this whisky. 87 Points

Wiser’s Legacy (Hiram Walker & Sons):

Legacy is another highly-awarded whisky, having won both Whisky Advocate’s Canadian Whisky of the Year in 2013 and the World Whisky Awards Best Canadian Whisky in 2011. It was released in 2010, is available in both the US and Canada and sells for about $45. Legacy is a predominantly rye-based whisky, with a little barley malt as well.

Nose: Rich and oaky with a sharp rye spice, cinnamon, toffee and dust.

Palate: Bursting with lots of sharp rye spice, toffee, wood, dried fruits, pepper, and a little green apple.

Overall: This whisky stands up to its reputation. It was easily the favorite at the tasting, and took top points in my book as well. 90 Points

Alberta Premium Dark Horse (Alberta Distillers):

Dark Horse is one of the newest releases from Alberta Distillers, makers of the very popular Alberta Premium. This particular whiskey, however, takes a bit of a detour from the standard Premium which is one of the very few mass-produced 100% rye whiskies on the market in Canada (DH has has a small inclusion of corn, under 10%). Dark Horse is an extremely rich whisky, and out of all of the whiskies on this list, reminds me the most of something that may come out of America.

Nose: A lot of rich vanilla and toffee notes, rich dark fruit, orange peel, and a dusty rye spice.

Palate: More of that sweet wood-baked vanilla and toffee (reminiscent of many American whiskeys), fruits and pepper, dried figs, molasses, and plenty of robust rye notes.

Overall: For under $30, Dark Horse is a great value whisky and offered a very unique perspective to this tasting lineup. Only available in Canada. 86 Points

Wiser’s Red Letter (Hiram Walker & Sons):

So the story goes, in the years following the American Civil War, Red Letter was one of the most sought-after whiskies in Canada. In 2007, Hiram Walker & Sons brought the whisky back to life to commemorate the 150th anniversary of J.P. Wiser. Since, Red Letter has become a limited edition annual release. The whisky is aged for at least 10 years in American Bourbon barrels and is finished in virgin white oak casks. It’s a Canada-only release and sells for about $100 (making it the most expensive whisky of the tasting by a long shot).

Nose: Rich vanilla, honey, dried fruits, baking spices and toffee come together into an evolving bouquet.

Palate: Lots of sharp dusty rye spice, vanilla extract, caramel sweetness, hot white pepper, a hint of chocolate and a spice-driven finish that almost gets a little tropical at points.

Overall: This is a complex whisky that continues to develop as you drink it. Though, for $50 less, I’d take the Legacy in a heartbeat over Red Letter. 89 Points

Interested in learning more about Canadian whisky? Check out Davin de Kergommeaux’s very informative website, CanadianWhisky.org, and his even more in-depth book, Canadian Whisky: The Portable Expert.